“This is a must-read for those

who love Yosemite

and its place in the American tale.”

Stephen Shackelton,

Former Chief Ranger, Yosemite National Park

Director, National Parks Institute

The riveting story of how FDR and thousands of unemployed Americans created today’s Yosemite National Park.

This is a special book, for many reasons.

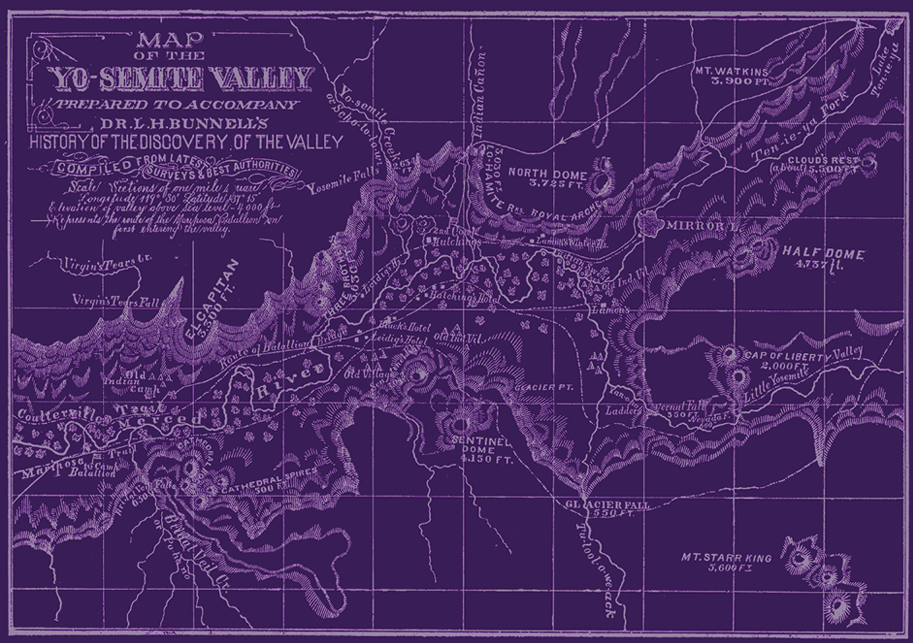

Yosemite’s transformation, in the 1920s and ‘30s, from an untamed wilderness embodying the lofty conservationist ideals of John Muir and Teddy Roosevelt, into the modern preserve and accessible wonder of the world it is today, is [a] key piece of narrative we’ve been missing.

Until now.

John Broesamle, an acclaimed historian and author of many academic and popular works, has brought this untold chapter of Yosemite’s evolution during FDR’s New Deal to stirring and vivid life.

Excerpts from the Foreword by Mark Frost

The Press at California State University, Fresno

Author John Broesamle was professor emeritus of History at California State University, Northridge, where he taught for thirty-two years. He held a Ph.D. in history from Columbia University. A political and social historian of modern America, he also wrote about and taught environmental history. Broesamle was a prolific and passionate author, and Transforming Paradise was his tenth and final book. He died on June 17, 2023, after a five-year battle with pancreatic cancer. The Press at California State University, Fresno accepted the manuscript for publication just weeks before his death, and it is being published posthumously in partnership with his family.

Broesamle had a lifelong association with Yosemite. As visitor for more than 80 years and as trained historian, he provides a living link between Yosemite during the New Deal era and the Yosemite of today. His family was one of the original Tuolumne Meadows “old-timers,” a community of teachers who spent entire summers there. His parents taught him to fly fish, a lifelong calling he fostered in his children and grandchildren. He also saw it as a vehicle for imparting values and ethics; the fly-fishing life became the perfect symbol of his abiding commitment to tread lightly and humanely on the planet. He met his wife, Kathy, during one of the many college summers they both worked in the park.

Broesamle’s other “home” was the Ojai Valley, where his decades of nonprofit environmental leadership resulted in the creation and restoration of large open space preserves, as well as a community chest of more than a million dollars to protect and sustain the environmental quality of the valley. Broesamle’s environmental work over the decades earned him the reputation as “conservation giant.” His hands-on work evokes the very spirit of much of what the New Deal accomplished in Yosemite.

In many ways, this is a tale that only John Broesamle could tell.

About the author

Explore chapter outlines

-

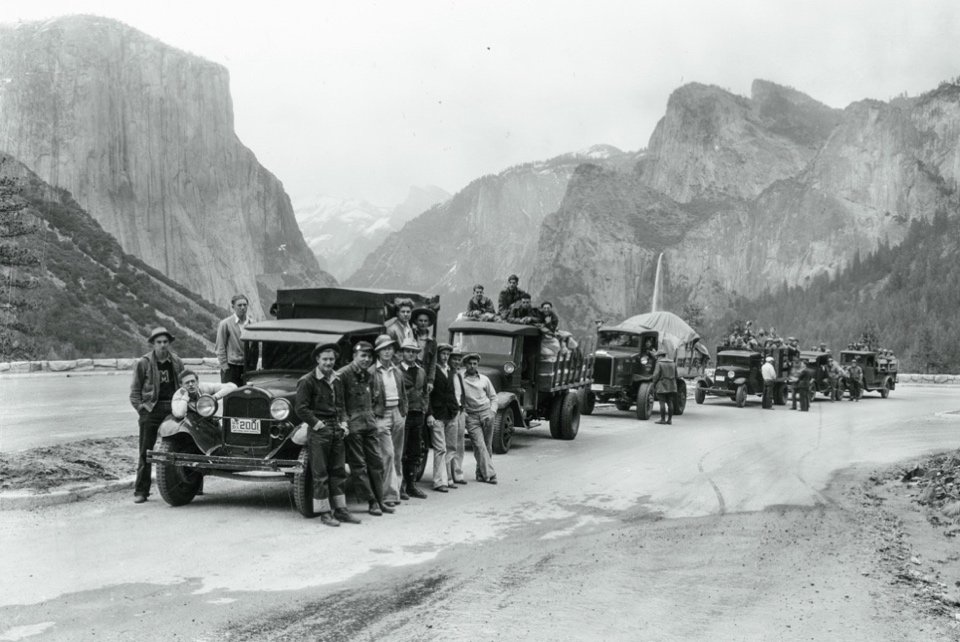

These several preliminary pages describe what it would have been like to cross Yosemite by car at the height of the New Deal. The roads were so nightmarish that some drivers panicked and froze at the wheel. Signs of New Deal activity would have been everywhere, though, including highway projects that produced the roads we travel today.

-

Before the Great Depression, the National Park Service and the park’s concessioner cooperated in attracting as many tourists as possible to Yosemite. Yosemite Valley became an entertainment zone featuring the nightly Firefall, a zoo, miniature train rides, and an annual rodeo. With more visitors came more stress on natural resources, calling into question how to balance preservation against unprecedented human impact.

-

Coming into the presidency at the height of the Great Depression in 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt laid plans to conserve natural resources while conserving human lives. He directed that the federal government put tens of thousands of unemployed, destitute Americans to work in the national parks. Initially, the chief emphasis was on forestry, a personal passion of the president’s.

-

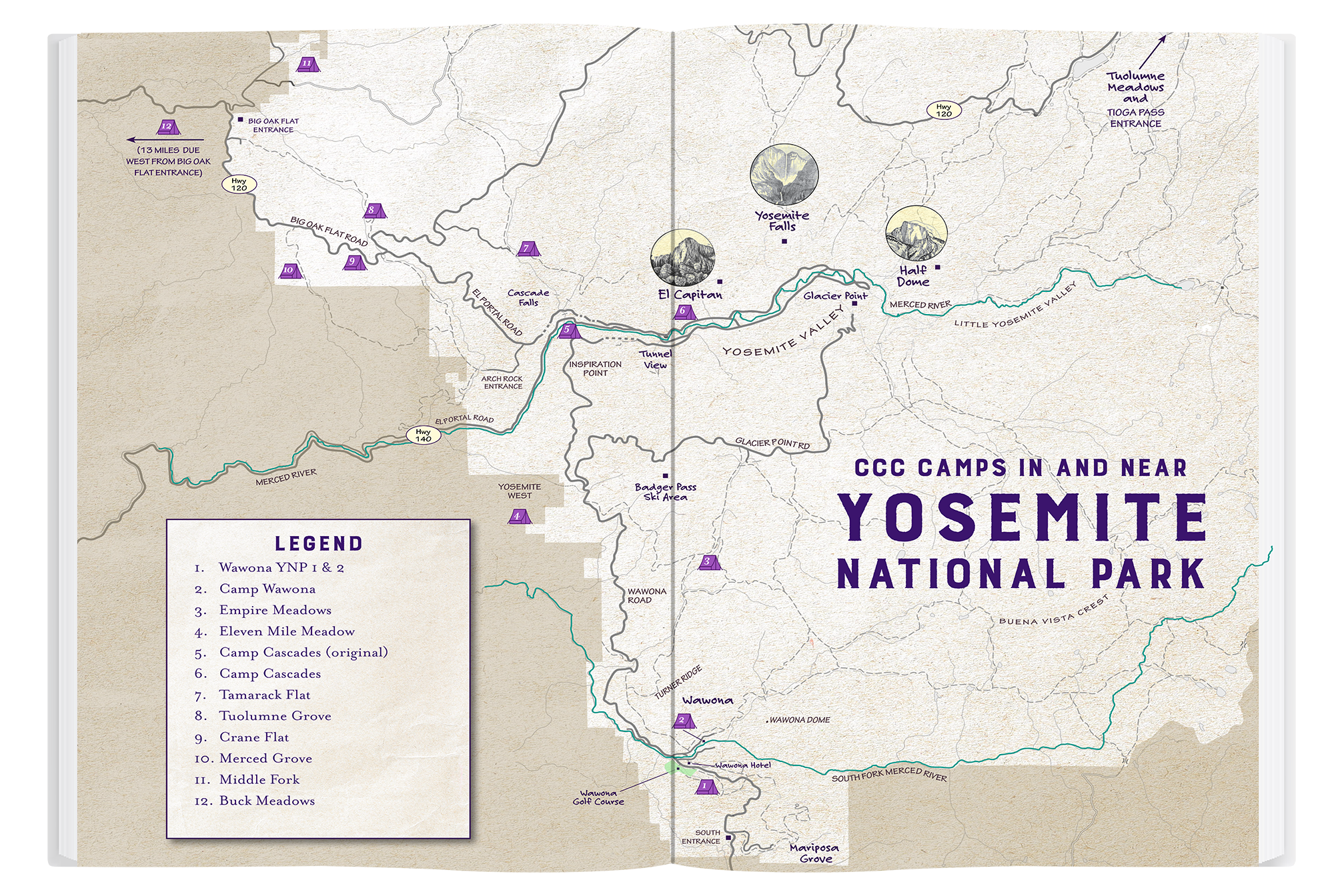

For Yosemite, the mainstay of this “work relief” program was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Some 8,000 young men ages 17 to 25 served there between 1933 and 1942. They came disproportionately from recent European immigrant families and from the South. Many others were Hispanic. And, in Yosemite, the CCC made a rare effort to integrate African Americans.

-

The park’s road system when Roosevelt took office had just begun a transition from narrow, snaking wagon tracks to modern highways. The New Deal poured in resources to speed up the process (while creating yet more jobs). Key decisions occurred on how to build highways in a way to avoid scarring the park’s iconic scenery – and, where that proved impossible, whether to build them at all.

-

Additional federal agencies began to enter Yosemite in 1934, including the Public Works Administration, which built massive projects still in use today. The CCC took on smaller-scale construction projects, fire prevention, and firefighting. It also battled a tree pandemic – white pine blister rust. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited the park’s backcountry, a camping trip that became one of the highlights of her life.

-

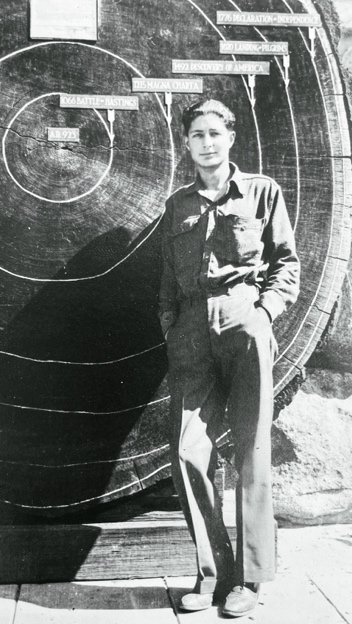

The standard books on the Civilian Conservation Corps shortchange the human element. Focusing on the CCC in Yosemite to bring the story to light, this chapter draws on the “newspapers” that each camp produced, as well as on original correspondence, interviews, and personal memoirs.

-

Large-scale construction peaked, including development of the Badger Pass ski complex and other recreation projects. Efforts were also mounted make Yosemite look “prettier” – for example, the Fern Spring project. All this raised a question: How refined, as opposed to natural, should the park be? A national debate ensued about parks in general, with wilderness advocates questioning the conventional wisdom.

-

After 1937, Yosemite was beset by a series of disasters, including a massive flood that year that temporarily undid much of what New Deal programs had accomplished. After visiting Yosemite in 1938, President Roosevelt twice tried to make the CCC permanent, failing both times. Once World War II broke out in Europe in 1939, budgets for domestic programs like the CCC fell as the nation prepared for war. In 1942, the New Deal ended in Yosemite.

-

This final chapter traces the legacy of the New Deal in Yosemite down to the present. It focuses on what endures, especially the environmental ethic of the 1930s and the infrastructure legacy. The chapter also shows how things have changed. It tracks themes from the 1930s that continue to challenge us today – global warming, forest health, wildfires, and the question of how to balance visitation with resource protection. Finally, the chapter traces the later lives of those – from FDR to the young CCC volunteers – who made up the human side of New Deal Yosemite.

Over 40 photos, many of which have never been published before, and a custom map capture this pivotal moment in Yosemite’s history.